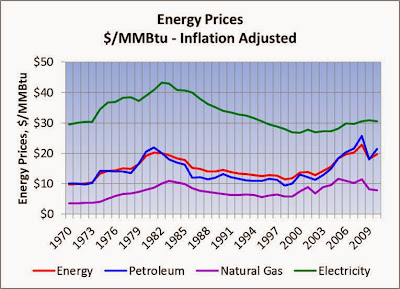

There are several points to make about energy prices. First, energy prices in the United States, based on all forms of energy at the retail level, reached their peak in 2007, at $22.79/MMBtu. Second, by 2010, energy prices had fallen 13% below the peak, and, in 2013, are heading back up. Prices in the chart below are expressed in inflation adjusted 2011 dollars.

A third point is that overall energy prices track petroleum prices very closely, demonstrating the enduring dominance of petroleum in our economy. Sustained high prices for energy in our economy are impinging on overall economic activity and employment. In 2013, energy prices are nearly twice what they were in the 1990's.

Our energy picture presents a fundamental challenge for the country's long term economic growth and prosperity. As has been presented in earlier blog posts, overall employment in the United States is 98% explained by energy use and petroleum prices. The great recession of 2008 caused a downdraft in employment, with a return to pre-recession levels not likely to take place until 2018.

Petroleum remains a significant force and commanding presence in our economy. Petroleum prices appear to drive overall energy prices in the economy. Our ability as a nation to influence petroleum prices has slipped from our grasp, with emerging countries such as India and China driving up and sustaining high levels of global oil demand. It has also been discovered that Asian countries have a lower elasticity of demand to price compared to developed countries. Asian countries, in other words, are more resilient to high prices than in the United States. The implication is that we are captive to market forces acting on petroleum beyond our control.

In addition to a loss of our ability to influence oil prices to our favor, it appears that we have also entered a new higher energy price plateau that has caused our economic fortunes to dim. Higher energy costs have caused demand to be tempered along with a reduction in economic activity. To sustain the economy requires reducing energy costs, increasing energy use and increasing energy efficiency and productivity.

Creating a more robust, resilient, equitable and sustainable economy can be accomplished, although it won't be without its challenges. To have a growing economy, even at moderate growth rates, requires a combination of low cost energy, increased energy consumption, and continuous improvement in energy efficiency and productivity. To regain control over our economic future, to unshackle ourselves from the vagaries of foreign markets and their associated high demand and high price regime, requires increasing the mix of less volatile and domestic sources of energy.

Petroleum and equivalent liquid energy products constitute approximately 36% of our energy use in the United States. This points to the great utility of petroleum and equivalent liquid fuels, which is difficult to replace or find substitutes. Significant efforts have been expended to produce liquid fuels, including ethanol and other biomass based liquid fuels. These efforts have been challenging due to poor energy balances and high costs. In addition to trying to alternative liquid fuels, significant efforts are underway to increase transportation efficiency with hybrids and other technologies, and introduce alternative fuel vehicles, considering electric cars and hydrogen vehicles. All of these technologies are expensive, may have performance challenges, and can require significant infrastructure investments. Finding a lower cost alternative to petroleum with equal or better utility is one of the most difficult challenges facing our economic future and well being.

The boom in natural gas in the United States has been quite beneficial to the economics of electricity generation and reducing the country's carbon emissions. The cost to produce a kilowatt-hour with natural gas in late 2013 is approximately 30% less than the cost to produce an equivalent kilowatt-hour from coal. This is due principally to the significant increase in natural gas production due to fracking, which in 2013 accounts for approximately 28% of the natural gas supply in the United States. The increase of natural gas supply drove prices down, with coal plants becoming uneconomic as a result.

For electricity production, the United States has shifted towards cleaner lower cost natural gas, and seen relatively significant increases in renewable energy, including wind turbines and solar power. The economics of both wind and solar have improved dramatically over this time period as well, with wind competitive with coal and the solar becoming competitive in extremely large deployments in sunny Western states.

The addition of renewables to the German grid, for example, are wreaking havoc on standard utility economics, in new and unexpected ways. Renewables are capital intensive and have zero fuel (marginal) costs. In a standard utility economic model, wholesale generation prices are set by the marginal cost to produce the last kilowatt hour in each hour. Grid operators dispatch generation resources using a system called economic dispatch, dispatching the lowest cost power plants first. Baseload powre plants have typically been nuclear power plants and coal plants, which had the lowest marginal operating costs and basically ran most of the time. Next up historically, covering the shoulder portion of the demand curve, would have been natural gas power plants.

Historically, heat rates and fuel costs for natural gas plants placed them at an economic disadvantage to coal plants. With the advent of fracking, driving down natural gas costs, and continuous improvement in the efficiency and heat rates of natural gas power plants, especially combined cycle combustion turbines, gas plants are have lower marginal costs than coal plants in the United States. As such, natural gas plants are displacing coal plants in the economic dispatch order in the United States. For several hundred hours per year, when the highest demand occurs, grid operators typically dispatch the highest marginal cost plants, including oil and diesel power plants.

Wholesale generators are compensated for their electricity production applying the marginal rate in each hour to all electricity produced in that hour. Based on historic patterns, this approach has been understood, and investments in generation assets have been based on this economic construct to cover plant fuel, O&M and capital costs. This economic paradigm, in place for decades, however, is going through a radical and disruptive change, with the introduction of non-dispatchable zero marginal cost renewables, and the introduction of demand side / distributed generation resources.

In locations as diverse as Germany and Texas, with independent grids and high penetration of renewable resources, grid economics have been upended. At times, on both grids, negative wholesale pricing was used to discourage power production. This occurred at times when non-dispatchable renewables were operating at full blast, typically a very windy period, and demand for power on the grid was at a low point, typically at night. In addition to negative pricing, grid operators also shut renewable plants down. The effective of negative pricing impacts both renewable and conventional power economics.

In Germany, the low marginal cost of renewable power is being applied as the basis for compensation for conventional power plants. In addition, the operating hours of natural gas plants are being cut back with the increased generation by renewable power. Renewable power plants are given preference on dispatch, to the chagrin of conventional power plants. The earnings of power companies in Germany have been significantly reduced. E.ON AG, for example, is suffering reduced earnings year over year, with a loss reported in the third quarter of 2013. It attributes the losses to poor economic performance of natural gas resources and the priority given to renewable power.

The economic impact of renewable power is disruptive in two ways. First, renewable power plants are allowed to operate when the wind blows and when the sun shines, given preference on operation over other resources. This cuts into the operating hours of standard power plants, reducing their capital cost coverage ratios. The second impact is the reduction in marginal costs applied to conventional power plants. Renewables are shifting marginal costs downward at times which were at once higher cost regimes on the dispatch curve. this is reducing the revenues for conventional power plants, hurting their economics.

The other area of concern to utility companies is the devolvement of customer energy demand associated with expanding distributed generation, increased efficiency and greater demand response, all of which reduce utility revenues. The combination of solar power, fuel cells and improved efficiency reduce the revenues associated with customers that implement energy reduction initiatives. As such, there are fewer kilowatt-hours sold, and fewer kilowatt-hours to spread fixed costs of operating utilities. As a result, utilities have to increase the rates they charge for electricity, to compensate for fewer electrons being sold. The customers that have taken advantage of solar and efficiency incentives, increasing electric rates have less of an impact than those customers that have not improved their efficiency or reduced their load through distributed generation.

As rates go up, and efficiency and distributed generation costs go down, incentives to switch away from the utility increase, and more and more customers will further reduce their electricity purchases from monopoly utilities. In many parts of the United States, utility companies have already had to abandon their generation business, focusing on transmission and distribution. Many utilities are investor owned utilities, with their capital sourced through public capital markets. As their revenue models are called into question, and electric revenues are flat or declining, utilities may hit tipping points, where regulators won't support ever increasing electric rates applied to dissipating electric sales. At that point, investors may run for the exists, destroying the IOU utility compact put in place nearly a century ago. This is getting interesting.

No comments:

Post a Comment