Short Piece Written in Comments Section in Response to Post by Jo Confino, Executive Editor of the Guardian, titled: "Sustainability movement will fail unless it creates a compelling future vision"

Ultimately, to survive, everything thing we do will have to

be sustainable. Everything. Throughout history, societies have faced

calamities, to which their collective response made all the difference between

survival or collapse. In most cases,

societies were unable to perceive much less respond to their inherent

unsustainable ways of living, such as the Mayans, Easter Island or the Anasazi. Their societies were based on unsustainable

and precarious systems of life support tied to the environment. In some cases, challenges have been recognized

and addressed, by perceptive and strong governments which was able to identify the problem and implement solutions.

The Japanese in the 17th century were faced with extraordinary

challenge of galloping deforestation. The

government instituted policies including using less wood for construction,

putting in more efficient heating stoves, and switched to coal from wood for

heating. Japan is currently about 70% forested. In a more recent century, the world did come together to address

CFC’s.

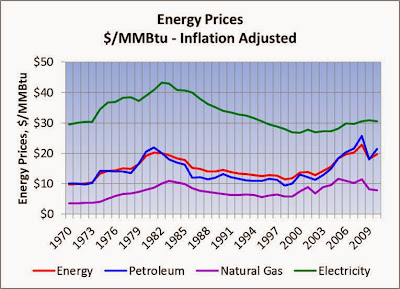

As seen in the United States and Europe, our carbon

emissions have come down over the past five years. Some may say we have exported our carbon

emissions to Asian countries. That can

account for some of the change, but it is also important to look at reduced

miles being driven, higher efficiency of cars, the switch to lower carbon

natural gas from coal in the United States, and the growth in renewable sources

of energy in Europe and the United States.

The US and European economies are responding to higher oil prices, which

has reduced the level of economic activity and reduced deleterious

environmental impacts. This provides a

clue to our future and solving the problem in two respects. First, economies of advanced countries do

have a higher elasticity of oil price to demand than Asian countries. Second, higher oil prices result in lower

levels of economic activity, increased efficiency, and reduced environmental

impacts. The earth is telling us to cut

back on energy, and we are. The pace of

the cut back may not be as steep a glide slope as what is sought, warranted or

needed. The implication is that we need

to do something to (1) steepen the glide slope in developed

economies; (2) reverse emissions growth in developing countries; and (3)

address severe economic and well-being inequities around the world.

Governments will play a critical and pivotal role in

turning the tide towards and accelerating the move towards a more sustainable

economy. The challenge with a capitalist

system, well established in the literature and through practice, is the

frequent absence of externalities, short time frame decision horizons, and

boundary conditions that do not address social issues such as global inequity. Nation states have a hard time being first, to take the lead on tackling large issues. The move to

address deforestation in the United States, for example, began with State and

regional initiatives to set aside parkland in the early 20th

century. We can also see more recent

examples of localization of environmental initiatives with RGGI in the

Northeast, the carbon trading initiative in California, and the implementation

of renewable energy standards in selected states, representing just a few of many excellent examples.

Ultimately, realizing a sustainable economy is in the

interest of business, governments and individuals. Without sustainable resources, economic decline, which has already begun, is inevitable, and will be inexorable and painful. Forestalling initiatives

which align our policies and investments to be consistent with a move to a

sustainable economy is not in our best interest. Having a

sustainable economy is not inconsistent with our economic interests, in

fact, ultimately it is 100% consistent. This

central tenant, that increased sustainability and increased economic well-being

are one and the same, may perhaps be that new paradigm people are looking

for. The interests of sustainability and

economics are not at cross-purposes, but are of one. Any society, any collective peoples

throughout time, who did not own and embed sustainability within their societies and cultures, did not survive.

Where does this unified theory of sustainability and

economics come from? Two

perspectives. One, mentioned earlier, is

understanding the history of societies that collapsed. The second is through understanding the

source of economic activity within our own economies, and extrapolating the

future risks our economy carries without integrating concepts of sustaining the

economy going forward.

The global economy has grown to an extraordinary degree over

the past several hundred years, tied to the level of energy entering the

economy. The level of economic activity is

explained by two things: one being the level of energetic inputs entering the

economy, and the second being the level of efficiency and productivity to which

those resources are put. Energy plus

Efficiency. If we want to grow our

economy, we have two choices, increase the amount of energy resources being

consumed, and/or increase efficiency and productivity. This is a very interesting finding, given

that we can have a growing economy with a static level of energy resources

entering the economy, as long as we improve the efficiency of resource

utilization. Second interesting finding

is that if we can economically migrate our energy systems away from

nonrenewable to renewable resources, while keeping energy use static and

improving efficiency, we can once again have a growing economy while

simultaneously reducing deleterious environmental impacts.

The cost of energy, however, plays an important role on our

level of economic activity. Higher

energy costs mean a lower level of economic activity, constrained by efficiency

improvements. If sustainable sources of

energy are a lot more expensive than non-renewable, then we will see a lowering

of economic activity. The pace of the

transition will be governed by the relative economics of the alternatives, and

the degree of incentives required to level the economic playing field, and the

pace of capital formation and its availability.

Fortunately, the economics of renewable energy are getting close to

being competitive without subsidies, with costs continuing to move down over

time with scale economies and continuous improvement. So what is the process to make this happen?

(1) Build a specific vision of where we want to be and when

in terms of sustainability. For example,

80% sustainable in 40 years. Great

detail and specificity by sector, end-use, activity, etc. is highly

recommended. (2) Identify specific performance metrics to track performance

along the way, such as proportion of renewable energy on the grid,

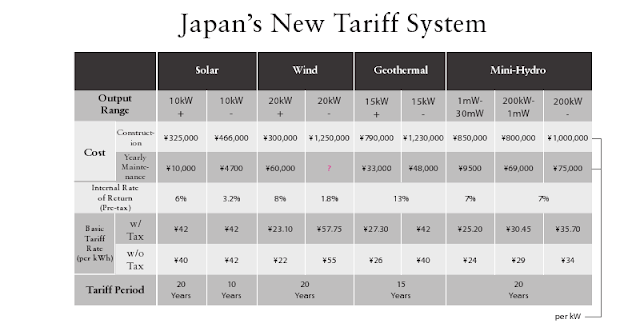

transportation, heating, etc. (3) Implement market incentives to encourage

private capital to make investments. Put

a price on carbon, set up carbon caps with trading, keep CAFÉ going, eliminate

subsidies on non-sustainable resources, reduce transition and market barriers

where possible, expand RPS requirements to every state, implement stretch and

zero net energy building codes in every jurisdiction in the country, implement

net metering tariffs in every state, increase CHP incentives, invest in

expanded public transit, etc. (4) Implement government initiatives to

transition government faster than private markets. (5) Expand incentives and

reduce market barriers for investments in energy efficiency and

productivity. (6) Incentivize investments

in technology innovation tied to renewable energy and efficiency and

productivity.

The prescriptive set of activities identified above are no

surprise to anyone involved in accelerating our transition to a sustainable

economy. The effort to adopt these steps

has to take place throughout society, to build a groundswell of activity that

is sound and impactful, building up from the local, state and regional levels

to the national and international level.

Significant progress has been made in specific sectors and in specific

countries, such as Denmark with wind, German with Energiewende, and Texas with

wind power. There are many more

examples, including renewable fuels and efficiency, but the pace has to

increase and the efforts have to expand.