United States Sovereign Debt

The Status

and Implications of United States Government Debt

January 14, 2017

Brad Bradshaw

President, Velerity

brad@velerity.com

A. United States Sovereign Debt Is Approaching $20 Trillion

United States government debt is approaching $20

trillion and more than doubled between 2005 and 2015, rising from $7.8 trillion

in 2005 to $18.1 trillion in 2015. This

rate of growth in our national debt is a concern. Is the United States becoming too indebted as

a nation? Will the burden of our

national debt subsume our economic vitality and future well-being? Is our government at risk of defaulting on

its national debt?

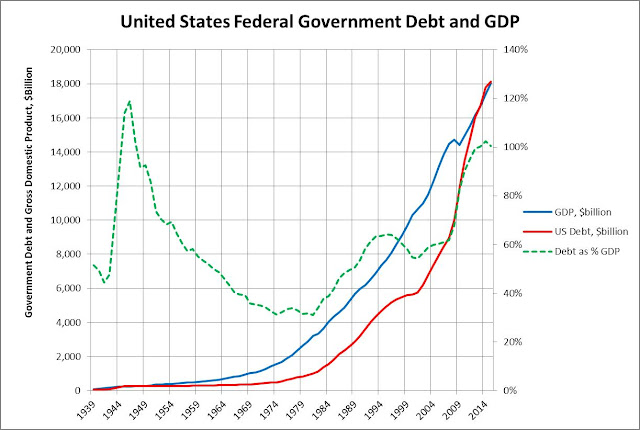

For nearly one-hundred years, as shown in Figure 1 below,

our national debt has moved roughly in lock step with GDP, albeit with a few exceptions. First, as seen in 1944, the government issued

significant debt as part of the war effort, with our national debt rising to

about 120% of annual GDP. From 1944 to

the mid-seventies, national debt remained in a relatively slow growth regime. Starting in the early 1980’s, however, debt

as a proportion of GDP began to rise, going from about 30% of GDP in 1982 to

about 65% of GDP in 1995. In the 1990’s,

government debt hit a relatively stable period, with reduced growth rates,

until 2002, at which time we see another uptick in the growth of debt,

accelerating for about a decade.

Figure 1 – United States Sovereign Debt

The 2007 recession created an extraordinary economic challenge,

with fears of total collapse of the global economy. Accordingly, the United States federal

government, peering down into an economic abyss, decided to significantly

increase liquidity in the market, through several means. Regardless of the specific mechanisms, the U.S.

treasury loaded up on a significant amount of debt, increasing the federal debt

79% over a 5 year period from 2007 to 2013, with the national debt increasing from

$9.0 trillion at the end of 2007 to $16.1 trillion by the end of 2012. This acceleration in the growth and

stratospheric level of our federal debt is concerning.

B. Our Growing Federal Debt has Placed the United States in Perhaps an Unwelcome Pantheon of Debtor Nations

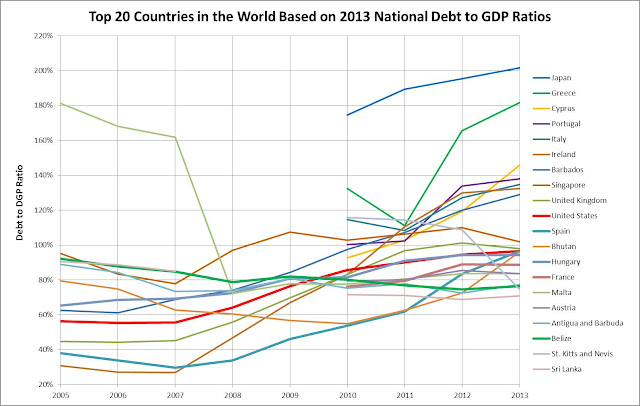

Figure 2 below provides some comparative context for the

United States’ level of debt. Based on 2013

data from the World Bank, the United States is 10th in the world

when compared to all other countries in terms of its level of sovereign debt

compared to GDP. The unwelcome pantheon of

debtor nations includes Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Spain, countries which

have faced significant challenges due to their debt being downgraded, and their

capacity to sustain borrowing being limited.

These countries were forced to significantly curtail government

expenditures, further extending and deepening economic downturns and creating

social chaos. Greece’s ongoing economic,

social and political strife provides an example of how poorly handled

(exploding) sovereign debt can impact a country and its people.

Figure 2 – Comparison of Debt to GDP for Selected Countries

The United States is also in the company of several large, established

economies, including United Kingdom, Italy, France and Austria, with equally large

and dangerous levels of sovereign debt. This

begs the question as to whether or not this level of debt for the United States

is sustainable, much less prudent and warranted.

C. Low Interest Rates Are Keeping Debt Servicing Costs Low, Will This Advantage Last?

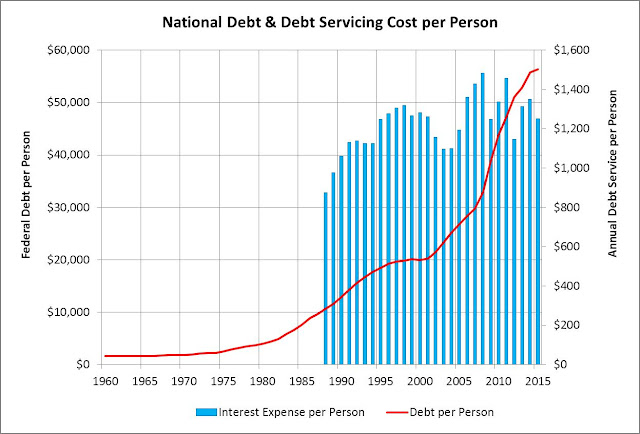

To bring the impact of our national debt down to a personal

level, the amount of indebtedness per person has risen from about $20,000 per

person in 2000 to $55,000 per person in 2015, nearly tripling over 15

years. The cost of this indebtedness per

person, however, has benefitted tremendously from the on-going low levels of interest

rates, with the interest expense per person keeping within a tight range in the

past 25 years, ranging from about $1,100 per person per year to $1,400 per

person per year, as seen in the blue bars in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 – National Debt Per Person and Debt Servicing Per

Person

It is extremely unlikely that interest rates will remain

this low going forward. The implied interest

rate associated with the United States’ debt servicing costs was a mere 2.23%

in 2015, the lowest it has likely ever been, and the lowest level for that past

thirty years of data evaluated for this analysis. This has been an extraordinary gift for the

citizens of the United States as well as the federal budget. Unfortunately, we know it will not last. We are currently entering a period of

tightening, with the Federal Reserve Bank already increasing interest rates twice

in the past twelve months, with further tightening expected in the next few

years.

D. What Really Is the Impact of Federal Debt?

Our federal debt is a function of the federal deficit, occurring

when spending exceeds revenues. The

federal government continues the policy allowing spending to exceed revenues,

and accordingly place the cost of running the government in the current year on

backs of future tax payers. Every

taxpayer in the country has a future and ongoing financial obligation to pay

for today’s government expenditures for many years into the future.

There are classic risks associated with this policy of

letting current deficits continue, placing future obligations on taxpayers, and

letting the debt rise to beyond currently stratospheric levels. The most significant is that interest rates will

rise, and the financial burden on each taxpayer may well double within the next

five years. This financial obligation

will crowd out other federal budget priorities, taking a progressively larger

share of the federal budget.

The debt obligation will also limit the ability of the

federal government to address future economic downturns, limiting our ability

to call upon fiscal and monetary policy.

There may be a point in time when the high level of debt and associated

obligations negatively impact the government’s debt ratings and borrowing

capacity.

At a more fundamental level, however, federal debt is a shift

in wealth from taxpayers to investors. As

a result of federal debt, taxpayers lose control over their own financial well-being,

and have less disposable income to spend or invest.

At the end of the day, the federal government is asking

taxpayers to invest in government operations, with the implied promise that, from

a social perspective, these investments will generate greater value for society

going forward than the associated cost of those investments. The unfortunate reality is that the

government’s expenditures at the margin are not likely to generate greater

value than the cost of those investments.

This places a drag on the economy, a parasitic burden from a value

generating perspective.

This investment drag on the economy is also additionally burdened

by the reduction in the velocity of dollars in the economy caused by the

inequity and imbalance associated with taking money out of the hands of

taxpayers and placing it in the hands of bond investors.

E. Conclusion – Where does this Leave Us?

The big picture for the United States associated with this

high level of debt is troubling. If we

face another economic downturn, we may not be able to overcome the economic challenge

with limited access to fiscal or monetary tools. We may be entering a new economic phase, similar

to Japan, in the clutches of a struggling economy for decades, with no apparent

solution.

Historically, a growing economy coupled with an increase in inflation

has been the approach to bring a country’s indebtedness in line with its

economy. The 1990’s was a time when our federal

government was able to bring our expenditures in line with tax receipts. It is going to be a fundamental imperative

that we return to a period of reducing government expenditures and/or raise

taxes to address this imbalance and step back from the debt precipice.

Additionally, it would be useful for our federal government

to make expenditure decisions that explicitly take into consideration the long

term value creation or destruction associated with budget line items, to shift

the mix of government expenditures, at the margin, to have a greater positive impact

in terms of value creation and on our future well-being.

Our federal government should also implement tax and expenditure

policies that encourage greater investments across our economy in value

creating investments and activities, and away from parasitic and value

destroying investments. The absence of

an explicit understanding and of having a policy of encouraging value creating

investments will result in a long and unsatisfying economic malaise and economic

hopelessness for the United States.